I never really wanted to be pregnant (I was relieved to read that AfrIndie Mom never did, either: I take neurotic comfort in the company of others!). I'm a medical wimp. I have major stress about even minor medical procedures, require tons of TLC during office visits, and all the times I have fainted have been in medical settings (and some of those fainting episodes have happened while I've been thinking "gosh, everyone was right. Having a cavity filled is really no biggie. It doesn't hurt at all....[faint!]). So pregnancy just didn't seem to be my cup of tea. And over the years, lots of little things seemed to push me towards adoption:

- once I was in Kinkos when someone was copying flyers for an adoption agency's open house on international adoption, but I was too shy to ask her for a copy.

- in Fall 1995, I read a student essay on the documentary about the dying rooms in Chinese orphanages and the thought of children in orphanages abroad really stayed with me

- one of my college classmates adopted three children in China (her elder daughter first, and then younger twins several years later), and each of her adoption trips got written up in our class notes

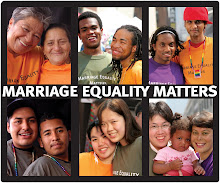

these all look like pretty inconsequential things when I write them out, but they were all moments where adoption just seemed to come into my mind, and not leave. And as we thought about getting ready to have childrem--and thought, and thought, and thought, as it was not clear to us when would be the right time to try to have a child, what with two careers and one or two large chronic health problems between us, so it was a long, difficult but ultimately emotionally rewarding journey to the moment we could say YES, this is the time when we both want to add a child to our family--adoption just felt right. It felt like a calling. I don't know if it was easier to come to this sense of calling because we're a queer family, but the issue of choosing your family has always made sense. We value our bio families, but we also value the family we choose, and all those relationships are a part of what is family to us. So there wasn't a lot of craving of bio ties to a child (although Politica might have a slightly different take on this, but that's her story to tell: suffice it to say that she made the difficult decision not to pass her genes on to a child because of some heritable medical conditions. That was something she grieved, and it's another part of our story.)

So I'm skipping the difficult year and a half in which the decision to have a child got made. Those are stories for another time. So having decided to forge ahead with an adoption, the next decision was how to adopt. This is a tough decision. Adoption isn't easy, and there are many considerations: international or domestic; public or private; fost-adopt or adopt. There are layers and layers of bureacracy, lots and lots of fees. I've read lots of blog debates about the ethics of international adoption, and it's commonly asserted that people choose international adoption because they don't want to deal with birthfamilies. That's probably true for some people, but it's not true for everyone. We chose international because we found an agency who understood our family and could help us through the process (which involved one of us adopting abroad and the other adopting in the U.S.). We chose international because it just felt right. We travel a lot, we have family spread around the world, and international adoption just felt right.

That all said, we didn't research domestic adoption very thoroughly, and reading I've done at blogs like Boomerific, This Woman's Work, and Peter's Cross Station has made me realize that there's a lot to learn about domestic adoption. A public adoption didn't seem to offer the chance to have a younger child with the kinds of health issues we felt comfortable walking into; a private adoption seemed to raise emotional risks that would have been hard for us. We had spent some very hard years trying to work though whether we were ready to adopt a child, and waiting for potential birthparents to read our letter was not something we thought we could handle.

A really hard part about adopting was making all these choices, choices which seemed to arbitrary and selfish, or choices which seemed so necessary yet could look like they're selfish to others. (Shannon's post today, responding to the same call from Sster, notes that having children is profoundly selfish no matter how you go about it, and reading that post as I edited this one made me feel better about these ramblings.) We were relieved to find an agency so easily, then obsessed about which country program (of the two the agency offered) to choose. We didn't have good criteria for choosing, and having to make choices was hard. All the choices had consequences, ones we would never know about (since choosing country A would have meant a different referral than country B). We didn't harbor any mystic notion that the Perfect Child for Us was Out There Somewhere (I once read a lifebook where someone explained that her tummy was broken and God sent the child to be born into the birthmother for the purpose of uniting her with the adoptive mother. I don't believe that any power is purposely placing children in families and homes where they cannot be raised in order to create an adoptive family half a world away, or even next door).

The other hardest part about adopting was how we presented ourselves as a familiy. We were out to our agency, and not out in the adoption process abroad. And sort of not out to the US government. I've read some stinging criticisms of gay couples who aren't out in the adoption process on boards like IAT and Discuss IAT, discussions which accuse gay couples of lying, of not being respectful of other countries' (homophobic) cultures, of not being respectful of birthparents who might not choose gay parents for their child. We didn't adopt in China because we didn't want to lie in our paperwork. We were truthful, in a way, although we left out some key truths. No mention of our Quaker wedding, no mention of our civil union. In the homestudy process we doubtless left out many other things...no mention of our biggest arguments, no mention of our biggest character flaws. I know, it's not the same...but it's hard to be out when the system you're working with doesn't even have a category for you. So I think the issue of outness and lying is a complicated one. And a hard one for gay families to negotiate in all kinds of ways, before, during and after adoption. It is hard for us to think about returning to CG's birth country--which we will do, no matter how hard--in part because we will have to face these issues all over again, this time, with a verbal child. This is a fuzzy area for me, one I am still thinking about, puzzling over the ethics.

One of the things parenting has taught me, time and again, is that the best decisions are difficult to explain to others. They are decisions that emerge from such a tangle of factors, and decisions that work for me and for us. They're not decisions that will work for everyone and I don't mean to be judging folks who have decided to be pregnant, or who have come to different adoption choices. This is all what worked for us, and I love reading the narratives of other choices. They show me possibilities.

Another interesting issue for us was naming, but I'll save that for another post (but if you want to read an interesting post on marriage and naming, head to Jody's.

3 comments:

you're the only other person i know in the world who understands why my medical squeamishness would prevent me from birthing a baby :) love. you.

I didn't know they allowed gay couples to adopt from China. There are some people who would say when you lie to adopt you are having in essence an illegal adoption. I am certainly not against a lesbian couple raisin a child but I don't agree with lying to adopt. It seems very arrogant and disrespectful to the real family who if they knew would most likely have not wanted that. And yes, when you go back to China with a little girl who can speak you will have to face the fact that you were dishonest. Not only that but blatantly disrespectful to her country of origin.

China now requires (but did not originally) adopting people (couples or singles) to sign an affadavit of heterosexuality. We might have pursued a Chinese adoption but when we learned about that particular requirement, we didn't. We didn't want to lie in our adoption paperwork.

It's not as simple as you might think to be a gay person dealing with institutions and laws that don't acknowledge gay families. Politica and I have had a religious wedding; we have had a civil union in Vermont. Simply answering the question "are you married?" seems to require what some would consider a lie or untruth no matter what answer we give.

Then there are all the institutions we deal with--everything from my doctor's office to the adoption agency to the travel agent to our workplace--which have varying abilities and desires to recognize the structure of my chosen family (and all of us who partner with adults, whether legally recognized or not, have a chosen family).

I agree with you, in part; I didn't want to do an adoption in China because of the subertfuge involved. And in general, the lesbians I know who are adopting are turning to China less and less because of that rule. But the issue of truth and lying is not as clearcut as it might be for straight people who are asked questions about their family (for one thing, people don't always know that a lesbian has a partner and thus assume we are single).

Post a Comment